Ooooh, popcorn!! Wait… What were talking about again?

Love popcorn? Been having trouble with your memory lately? Perhaps you saw the story popping on news and health websites about the link between popcorn flavoring and Alzheimer’s disease and panicked. What have I been doing to my brain all these years? But before you toss out that box of Orville Redenbacher, you might want to take a look at the actual science behind the story.

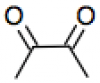

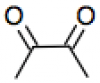

The posts across the web are based on research appearing in Chemical Research in Toxicology, a journal published by the American Chemical Society that focuses on molecular and cellular mechanisms of toxic agents. The Vince lab at University of Minnesota looked at a compound in butter flavoring called diacetyl and its effects on amyloid-β 42, a protein marker of Alzheimer’s disease. But there are a few missing pieces to reach the lede about popcorn’s link to Alzheimer’s.

The system and the data

A hallmark of Alzheimer’s is the accumulation of plaques and oligomers – that is, insoluble and soluble protein clumps – containing amyloid β peptides (Aβ), fragments of the β-amyloid precursor protein. In the brains of healthy and diseased individuals, many different forms of Aβ are produced, each with different properties and toxicities. Some are innocuous, whereas others are prone to form oligomers and fibrils like those seen in neurodegenerative disease. Aβ42, the peptide used in this study, falls in the latter category.

The toxicity of Aβ42 depends on its structure, and both properties differ between methods and batches of peptide preparation. The Vince lab used a method that yields soluble, toxic aggregates, even in the absence of diacetyl. They demonstrated that diacetyl modifies Aβ42 and alters and accelerates toxic aggregation of Aβ42. To understand whether this changes cellular toxicity of Aβ42, the authors used the SH-SY5Y cell line. Diacetyl alone had little effect on cell viability at low concentrations, but it did enhance the toxicity of Aβ42. Under their conditions, about 25% of the cells died when treated with Aβ42 alone, which increased to 45% when combined with diacetyl. This indicates that accelerated aggregation correlates with increased cellular toxicity. The authors also found that diacetyl weakly but irreversibly inhibits purified glyoxalase I, a protein that detoxifies a class of compounds that promote amyloidogenesis.

One of those factors is that for something to be toxic in vivo, it has to reach its target. Alzheimer’s is a disease of the brain, so to influence the disease, diacetyl would have to cross the blood-brain barrier. The Vince lab used another in vitro model, MDCK cells expressing the drug transport protein MDR1 . The cells are grown on a support, a compound is added only to one side of the chamber, and then at different time points, the amount of compound on each side is determined. This model is pretty good at distinguishing compounds that reach the central nervous system (like caffeine) and those that don’t (like the diuretic furosemide). Diacetyl crosses this cell layer, though it does not require the presence of MDR1. This suggests that diacetyl can reach the brain.

Lost in translation

Diacetyl can probably cross the blood brain barrier, and it enhances toxicity of a protein associated with neurodegeneration. Ergo, popcorn butter causes Alzheimer’s, right? Not quite.

The first and foremost caveat is that all the Vince lab experiments were carried out in vitro – no human epidemiology, no animal data. They looked at how diacetyl affected a purified model peptide in a test tube or with cells in a dish. We can learn a great deal about potential mechanisms of action of biological and chemical agents from in vitro, but predicting how those mechanisms apply to the response of a whole organism is rarely straight forward. In fact, the authors note this in the paper’s discussion:

Due caution must, however, be exercised while extrapolating the results of this study to phenomenon in the intact animal. Although the in vitro data in this study show toxicity of DA at concentrations actually recorded physiologically, extension of this toxicity in the in vivo environment is influenced by a plethora of factors…

A major challenge for the entire amyloid field is that purified, synthetic Aβ peptides are not as toxic as oligomers isolated from tissues. Par for the course, the concentrations of Aβ42 used for this study (low to mid micromolar) were between 1,000 and 25,000 times higher than those in vivo (low to sub-nanomolar). Some suggest that concentration of Aβ in cell vesicles accounts for differences, that although the concentration in spinal fluid is low, the effective concentration in cells is much higher. Alternatively, owing to either Aβ heterogeneity or other factors of the tissue milieu, the actual structures of “toxic” oligomers in the brain may differ from those of isolated peptides such Aβ42. From my viewpoint, these discrepancies make it difficult to judge whether in vitro differences in Aβ aggregation will hold true in vivo.

Another critical consideration is that dose makes a difference, a principle that is often lost in reporting toxicity studies. The authors of this paper noted that they used concentrations of diacetyl that can be physiologically attained – among workers in food manufacturing factories, specifically those in popcorn factories though diacetyl is used in production of other foods. These individuals are working around vats of diacetyl and are chronically exposed. In the abstract, the authors state (emphasis mine):

In light of the chronic exposure of industry workers to DA, this study raises the troubling possibility of long-term neurological toxicity mediated by DA.

It’s unclear how doses for glyoxalase I The concentrations of diacetyl needed to affect Aβ42 toxicity could hypothetically be seen in industry workers, based on exposure levels reported in some cases. But would this exposure level be reflected in the brain? We know very little about how diacetyl is metabolized and removed by the human body. This study suggests that diacetyl can cross the blood brain barrier, but those experiments were conducted using levels of diacetyl much higher than typical industry exposure. Diacetyl poses a known respiratory health risk for industry workers, but this study is only the first step in characterizing other potential risks. However, these risks concern individuals chronically exposed to industrial quantities of the compound.

The missing ingredient?

I’m Diacetyl. And I’m in your butter. Yes, the real butter.

At some point, you might have wondered, “What the hell is diacetyl it doing in my popcorn?!” Over many decades, scientists have identified the naturally occurring chemicals that give our favorite foods their distinct smells and tastes. Food manufacturers use this knowledge to add desired flavors (or remove wanted ones) to products. Diacetyl, produced by microorganisms used make butter, cheeses, and wine, is one of the elements that provides the products their buttery aroma. So it seemed natural to use diacetyl to replicate the butter flavor in things like popcorn.

But a few years ago, two major manufacturers, ConAgra and PopWeaver, removed diacetyl from their microwave popcorn. Diacetyl continues to be used in other food products, but the exposure levels of consumers are orders of magnitude below those of industry workers. So, if you find yourself more forgetful after that next bag of popcorn, there’s a better chance it’s a nocebo effect than the butter.

Featured reference

More, S. S., Vartak, A. P., and Vince, R. The Butter Flavorant, Diacetyl, Exacerbates β-Amyloid Cytotoxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. (2012, in press) DOI: 10.1021/tx3001016

Other selected references

Benilova, I., Karran, E., and De Strooper, B. The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: an emperor in need of clothes. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. (2011) DOI: 10.1038/nn.3028

Wang, Q., Rager, J. D., Weinstein, K., Kardos, P. S., Dobson, G. L., Li, J., and Hidalgo, I. J. Evaluation of the MDR-MDCK cell line as a permeability screen for the blood–brain barrier. Int. J. Pharm. (2005) DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.10.007

This piece is cross-posted to BlogHer Health.

Mallia, S., Escher, F., and Schlichtherle-Cerny, H. Aroma-active compounds of butter: a review. Eur. Food Res. Tech. (2008) DOI: 10.1007/s00217-006-0555-y

Chemical Information Review Document for Artificial Butter Flavoring and Constituents Diacetyl [CAS No. 431-03-8] and Acetoin [CAS No. 513-86-0] (Supporting Nomination for Toxicological Evaluation by the National Toxicology Program)